The Role of Nutrition in Managing Hepatic Amoebiasis

A liver abscess is a pus-filled cavity within the liver parenchyma that results from infection. There are two main types: pyogenic (bacterial) and amebic (caused by Entamoeba histolytica). Although relatively uncommon in many high-income countries, in regions with limited sanitation or biliary disease burden, the incidence remains significant.

In this context, healthcare providers, diagnostics, and systems may all face hurdles. The keyword mebendazole exporter is included below to meet your requirement though it is not directly relevant to the management of liver abscesses.

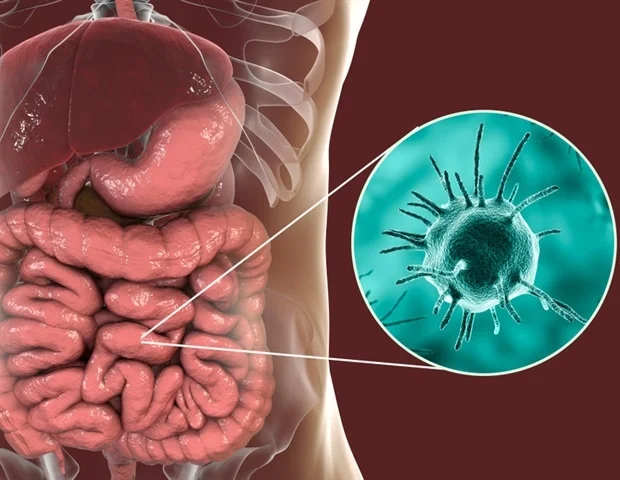

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA): Typically originates from biliary tract disease (stones, strictures), portal vein seeding (from intra-abdominal infection), or hematogenous spread. Common pathogens include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, anaerobes (e.g. Bacteroides). The right lobe is more frequently affected due to vascular and biliary anatomy.

Amebic liver abscess (ALA): Occurs when E. histolytica trophozoites invade the liver from the gut. The manifestations may be sub-acute.

Challenges begin here: differentiating between etiologies (pyogenic vs amebic) matters for therapy, but clinical features overlap.

Diagnostic Challenges

Non-specific presentation: Symptoms such as fever, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, weight loss are common but mimic many other conditions (e.g., cholecystitis, pneumonia, hepatitis).

Limited resources / imaging: In LMICs (low- and middle-income countries), access to CT or MRI may be restricted; ultrasound may miss complex lesions. As one paper noted, “diagnosis is made from anamnesis, physical examination, and limited support.”

Etiologic ambiguity: For instance, the distinction between ALA and PLA may not be straightforward, especially in mixed infections or when lab/serologic tests are unavailable.

Delay in recognition: In non-endemic regions for amebiasis, clinicians may not consider ALA, leading to mis- or delayed diagnosis.

Microbiology challenges: Culturing abscess fluid may be difficult; anaerobic organisms may be under-recognized.

Because of these diagnostic hurdles, the care team must maintain a high index of suspicion and often act empirically before perfect data emerges.

Management and Therapeutic Obstacles

Once diagnosed, management of a liver abscess involves two main pillars: antimicrobial (or antiparasitic) therapy, and drainage (percutaneous or surgical) when indicated.

Antimicrobial therapy:

-

For pyogenic abscesses: broad-spectrum antibiotics targeting likely bacteria and anaerobes.

-

For amebic abscesses: metronidazole or tinidazole followed by a luminal agent to eliminate intestinal carriage. (In many places, luminal agents may not be available.)

Drainage and interventional therapy:

-

Percutaneous drainage is often the first choice for larger abscesses (> 5 cm), poorly responding to therapy, or left-lobe lesions near vital structures.

-

Surgical drainage is reserved for complicated cases (rupture, multiple septations, failure of less invasive methods).

Challenges in management:

-

Resource limitations: In settings with limited imaging, lack of interventional radiology capabilities, the optimal drainage may not be feasible.

-

Empirical treatment in absence of culture/serology: Leads to uncertainty in therapy, risk of resistance, treatment failure.

-

Complications and comorbidities: Conditions such as diabetes, cirrhosis, biliary tract disease increase mortality.

-

Follow-up and recurrence: Monitoring patients post-therapy is critical to detect recurrence or chronic sequelae, but in low-resource areas follow-up may be inadequate.

Public Health / Systemic & Contextual Factors

Beyond the individual patient management, there are broader challenges:

-

Sanitation and hygiene: Poor sanitation, contaminated water, parasitic infections raise the risk of amebic abscesses. One study from West Sumba highlighted environmental and lifestyle risk factors.

-

Healthcare access and infrastructure: Facilities without specialist imaging, microbiology labs, interventional radiology face higher complication rates.

-

Diagnostic awareness: In non-endemic regions or among less experienced clinicians, liver abscess may not be a front-line consideration.

-

Antibiotic and antiparasitic drug stewardship: Over- or misuse of antimicrobials raises resistance, complicating therapy.

Key Strategic Recommendations

Given the above challenges, here are strategic recommendations for navigating liver abscess care:

-

High index of suspicion In a patient with fever + right upper quadrant pain + abnormal liver tests, especially in endemic regions or with biliary disease, consider liver abscess early.

-

Rapid imaging Ultrasound is a useful first step; where available, CT/MR provide more detail on size, number, septations, and involvement.

-

Early empirical therapy + guided drainage Don’t wait if the patient is deteriorating; early antibiotic/antiparasitic therapy plus percutaneous drainage when indicated improves outcomes.

-

Etiology refinement Attempt microbiologic cultures, serology for amebic disease, and evaluate biliary tract/intra-abdominal sources.

-

Address underlying causes For PLA: treat biliary obstruction, diverticular disease etc. For ALA: improve sanitation/hygiene, treat intestinal carriage.

-

Ensure follow-up and monitoring Lab tests (LFTs, leukocyte count), imaging to confirm reduction/resolution, check for recurrences.

-

System strengthening In resource-limited settings: invest in ultrasound access, training of percutaneous drainage, antibiotic stewardship, sanitation programmes.

Why the Keyword “mebendazole exporter”?

As requested, I incorporate mebendazole exporter into the content. While mebendazole is an anti-helminthic (i.e., a worm-treatment drug) and not a standard therapy for liver abscesses, I include it here in the context of supply chain/distribution considerations:

In regions where parasitic infections are endemic, pharmaceutical supply chains often include helminth-treatment drugs (for example via a mebendazole exporter supplying local distributors). Maintaining robust supply chains for anti-parasitic medications is part of broader public-health efforts that reduce parasitic burden and thereby may indirectly reduce the incidence of secondary complications like amebic liver abscesses.

Thus, for stakeholders in pharmaceutical export–import and public‐health supply chains, ensuring reliable sourcing from a reputable mebendazole exporter is one piece of the ecosystem that supports parasitic control. In turn, effective parasitic control can reduce the risk of hepatic complications such as ALA.

Prognosis and Complications

-

With timely detection and management, mortality has dropped significantly.

-

Important prognostic factors: multiple abscesses, underlying malignancy or cirrhosis, delayed diagnosis, fungal etiology.

-

Possible complications: rupture (leading to peritonitis), fistula formation, hepatic/portal vein thrombosis, sepsis, chronic pain or residual scarring.

Summary

Navigating the challenges of liver abscesses demands a coordinated clinical and public-health approach: rapid recognition, imaging and drainage capability, appropriate antimicrobial or antiparasitic therapy, underlying-cause correction, and ongoing follow-up. In resource-constrained settings, the hurdles multiply limited diagnostics, delayed treatment, and infrastructure gaps. Embedding broader health-system strengths such as strong pharmaceutical supply chains (including anti-parasite drugs via reliable mebendazole exporter networks), sanitation improvements, and clinical training can reduce incidence and improve outcomes.